The Cakewalk is one of the lesser known “grandparents” of Lindy Hop, alongside the Charleston, Black Bottom, the Breakaway and others. The cakewalk, however, was more than just a dance, it was also a subtle but powerful means of Black resistance to white supremacy.

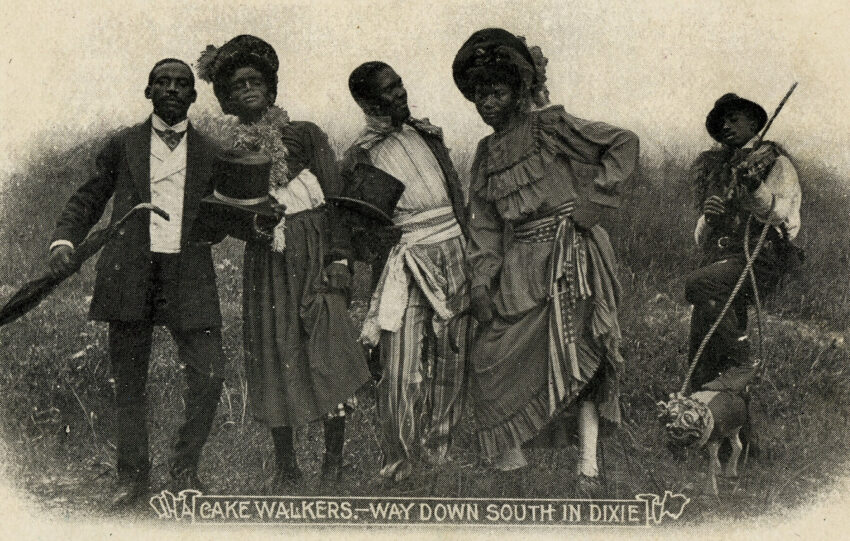

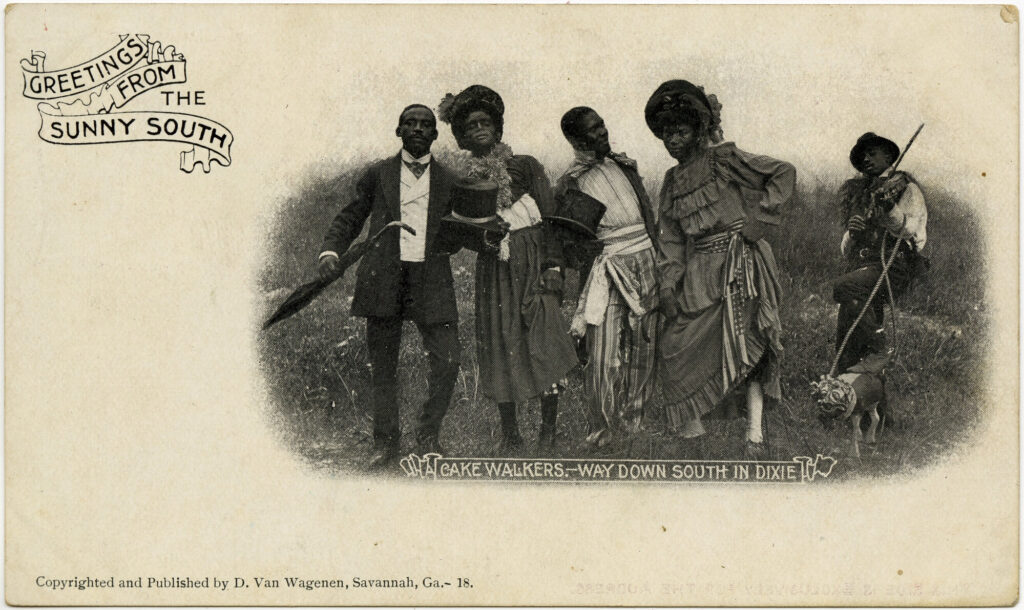

The history of the cakewalk goes all the way back to the time of institutionalized slavery in America, when many other forms of African music and dance were greatly restricted or forbidden. Slaves on Southern U.S. plantations were exposed to European dance forms such as waltzes that were done in ballrooms, with the men dressed in suits and the women in fanciful dresses.

As early as the 1860s, Black slaves recounted how they would promenade around, imitating and parodying the dance forms they saw their owners doing. These were called “cakewalks” because the couple deemed the best dancers were awarded a cake — which led to the phrase “taking the cake” or winning the prize. These cakes were sometimes provided by the white masters themselves to encourage these performances, probably missing the subtle critique of the dance. Skilled performers were expected to make even the hardest moves look effortless and easy, hence the contemporary usage of the term “cakewalk.”

This 1903 archival footage from the Library of Congress gives a sense of what the cakewalk might have looked like.

“The Spirit Moves” documentary has a longer clip featuring Leon James, Al Minns, and Pepsi Bethel performing their versions of the cakewalk.

Note the exaggerated high-stepping, stiff demeanor, and proud bearing of the dancers. There is some subtle cultural referencing going on here, being both a satire of the affected manners of white high culture and an expression of Black pride and joy by the performers. For a people enslaved, enacting a cakewalk right in the face of their oppressors might be understood as a prideful middle finger.

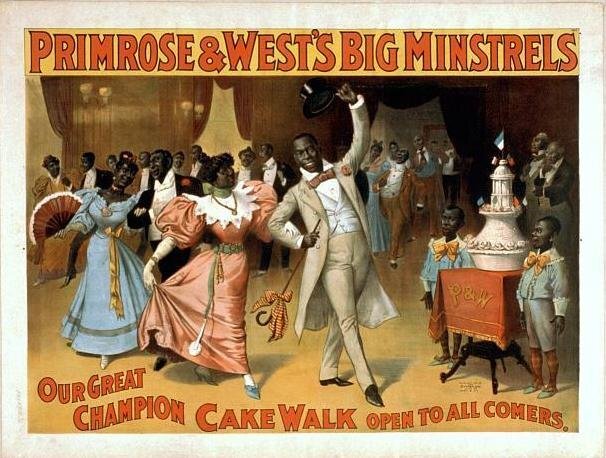

What’s amazing about the cakewalk was that it became so popular in America after the Civil War that white performers began doing their own versions of the cakewalk, typically in blackface, as part of minstrel shows. An even weirder twist was black performers, also in blackface, began performing their versions of the cakewalk for white audiences. As one historian Terry Waldo described it, “Blacks imitating whites who were imitating Blacks who were imitating whites.”

This was certainly not the first or the last time that Black people employed dance as a means of resistance to systemic racism. Brazilian capoeira, Puerto Rican bomba, b-boying in the Bronx, and footwork in Chicago are just a few other examples. But there is something so brilliant about the cakewalk as simultaneously satirizing their oppressors and celebrating their own culture.

If there is a more modern version, it might be ball culture from the Black and Latinx gay male communities in the 1970s and 1980s. But that’s a whole other essay that would best be told by someone from that community.

For now, whenever you hear the expression that “takes the cake” or something is a “cakewalk” remember how brilliant Black slaves employed the cakewalk as a subtle but powerful anti-racist tactic.

For further information see: