I spent most of my childhood in the San Francisco Bay Area. That sounds like a great cultural landscape to grow up within, with its diverse mix of races and peoples from all over the world. My reality was quite different.

Specifically I grew up in Pleasanton, California, a large town about an hour away from San Francisco proper. Culturally, it felt more like Kansas.

I had a strange mixed experience growing up as a second generation Filipino-American. During most of my daily life, I was one of the only Asian kids in my neighborhood and school.

Most kids — including myself — had no idea what a “Filipino” was. My sister told me a story about a friend of hers in elementary school asking her what she was. “Filipino,” my sister said. “Oh, we’re Protestant,” her friend replied.

There was almost no diversity that I saw around me. I don’t recall going to school with any Latinx or Black students or teachers until well into Junior High. And I didn’t have any Black or Latinx friends until college. My first Black professor was from South Africa.

I don’t recall ever having to explain to my class or other students my ethnic heritage or background. And we were never taught anything about my culture, despite Filipinos being the 2nd largest Asian group in America.

So I felt very anonymous growing up in my community among all my white peers and adults.

And then there were the weekends. That was when the family typically piled into our station wagon and headed to Richmond, to visit with our relatives. There was probably some occasion — like a birthday or holiday or a christening — but we didn’t really need an excuse to get together.

In Richmond, I felt much more like I was amidst a melting pot. There were Black people, Latinx people, Asian people, and so many Filipinos! It was like a different planet to me.

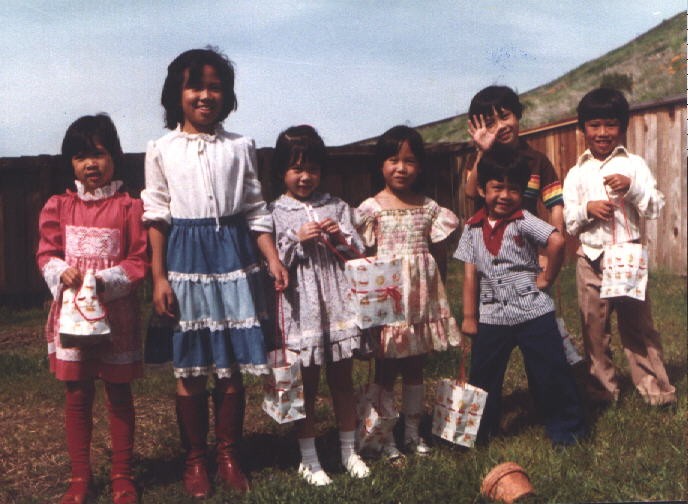

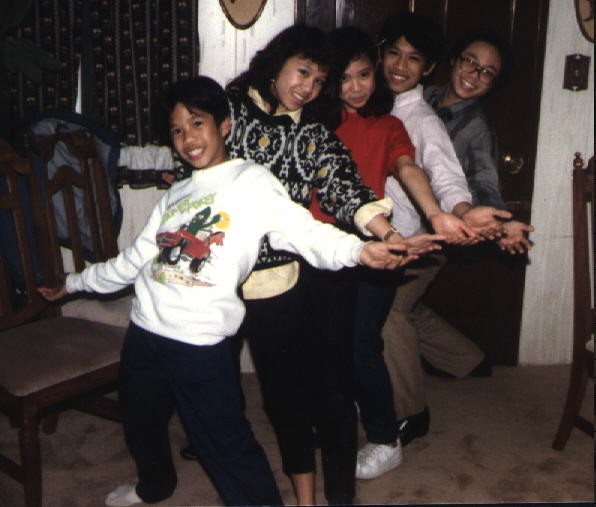

And there was always a crowd of brown people at my family parties. It was not uncommon for 30 family members and friends to be crammed into every room in the house, the backyard, and the garage. It was loud, boisterous chaos.

I remember idyllic hours playing with my cousins. There was a gang of six of us at the core, and others who would rotate in and out over the years.

It was there that I would get exposed to everything I knew about Filipino culture. I would like to say that we had cultural dances that we performed, local rituals that we observed, remembrances of the homeland, stories from our ancestors, and music that we listened to. But I would be lying.

Honestly, it was mostly food. Piles and piles of delicious Filipino food. Chicken adobo, pancit bihon, pancit palabok, fatty pork lechon, leche flan, pan de sal, and lots more.

At our parties we ate lots of food, watched whatever sport was going on that season, and hung out. The adults gossiped in Tagalog in the living room and played Mah Jongg in the garage until it was dark outside. The kids tore around the backyard and the neighborhood with zero supervision.

And then in the evening, my sister and I would reluctantly pile into the car and head back to Pleasanton. We were often crying as we were leaving.

My first real exposure to Filipino / Fil-Am culture was when I went to college at UCLA. There were Asians everywhere, and a zillion clubs, fraternities, non-profits, and events to participate in. I didn’t go to any of them.

I never felt at home among other Filipinos who weren’t my own family. I didn’t understand them, didn’t have a shared frame of reference, didn’t feel any real kinship with them. I felt embarrassed to know so little about my own country and culture. I couldn’t speak any Tagalog or any other Filipino dialect.

It was in college I first heard the insults of being a “Banana” (yellow on the outside, white on the inside) or a “Coconut” (brown on the outside, white on the inside) expressed toward people like me. I knew I was a fraud, mixed-up, ill-informed, and a poser.

And then I took my first trip to the Philippines in my early 20s. It was only then I started to feel some kind of stirrings of connection and identity, but also a profound sense of “otherness” being there.

It’s only recently that I’ve grown to accept my experience and mixed identity as totally normal. I’m not broken or confused or half-formed. All these influences are my culture. And while I wish I had a richer cultural connection to my immigrant roots, I don’t begrudge my family for how they raised me. They made the best choices as new immigrants that they could for themselves and their children.

And honestly, as epithets, being a Coconut doesn’t sound all that bad.