I’ve seen articles that have said roller skating was irrelevant since the ’70s. OK, so what have I been doing for the last 20 years? No, it hasn’t been irrelevant. Roller skating has continued to survive because of the African-American community and our ability to open up the culture to others who want to learn it.

Reggie Brown, 36 year old skater from New York [2021, source]

Each dance follows a pattern: it is introduced by Black dancers, criticized and banned as shocking and immodest, then forced into acceptance by sheer popularity, public demand, possibly years later, in a watered down or modified version, one which the general public can easily learn and perform. It is then part of American culture.

Margaret Batiuchok [1998, source]

As I learn more about the history of rhythm skating in the United States, I see many distressing parallels to the story of lindy hop. Both were born in Black urban communities, then became popularized by white participants who subsequently diminished those Black roots and artists.

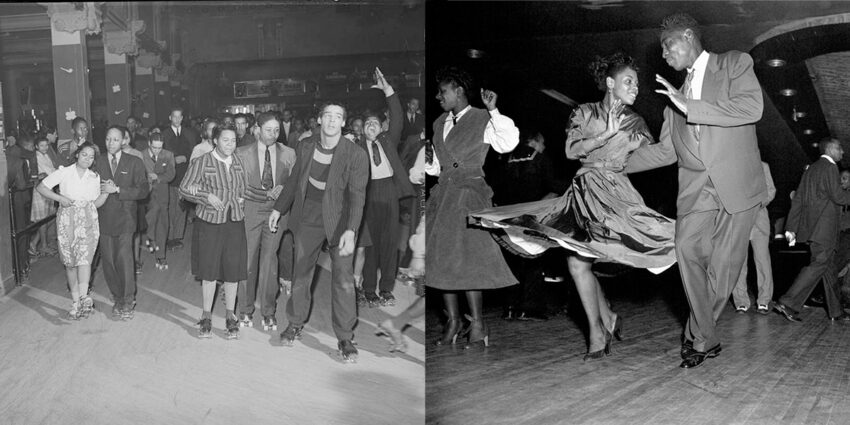

Rhythm skating is a form of dance done on quad roller skates with deep roots in Black communities dating back to the 1950s. Regional rhythm skating styles continue to this day, with skaters in New York rolling differently than skaters in Chicago, Cleveland, or Philly. Check out this video from SkateLyfe to see the wide variety of stylings from different skate crews from around the US.

Lindy hop, the grandfather of all swing dances, also traces its roots to the Black community, particularly Harlem, New York in the 1920s-1940s. There were many regional variations present in lindy hop from the Swing Era to the 1990s. The Texas swingout differed from the swingout in LA, New York or London. Ryan François gave an entertaining TEDx talk about this back in 2013. But with the globalization of lindy hop, most of those regional variations and styles have been washed away.

The Black spaces that incubated the artforms that became lindy hop and rhythm skating trace their roots to segregation. Roller rinks, like many public spaces in America, were segregated for much of America’s history. Rink owners shunted Black skaters to racially coded nights like “Soul Night,” “MLK Night,” or most commonly “Adult Night.”

Similarly, lindy hop originated in Harlem ballrooms like the Savoy, the Alhambra, and the Renaissance. These were spaces where African American men and women could express pride in their appearance, their style, and their culture, in the midst of a society where those things were not valued or represented.

If you don’t understand Jim Crow, you don’t understand lindy hop. The intensity behind their dance comes from being denied the rest of their lives.

Moncel Durden, dance historian [2020, source]

Cultural appropriation of Black art is a painful issue in both communities. In lindy hop that has manifested in how the Black roots of lindy hop have been largely diminished or boiled down to a few catchphrases, as well as the continuing marginalization of Black voices in the lindy hop scene.

In rhythm skating, appropriation has manifested in the social media portrayal of dance skating as something solely performed by young white girls, in skimpy tops and short shorts by the beach. Rarely is it depicted as an artform created and preserved in Black spaces by Black artists. Meanwhile, the continued destruction of roller rinks around the US, as chronicled in the powerful documentary United Skates, is taking away these vital spaces for the Black community to gather and create this art.

It’s hard to know how to respond as an ally and someone who benefits from Black arts like lindy hop and rhythm skating. At the very least we can acknowledge the history and elevate the work of the Black pioneers and innovators who gave us these artforms.

In the lindy hop world, there are groups like the Black Lindy Hoppers Fund, Collective Voices for Change, and the Frankie Manning Foundation that are working to preserve the Black roots of the dance. There are similar efforts to elevate and preserve Black skate culture, such as @bipocwhoskate. In the Bay Area, we are lucky to have BIPOC skate legends who still teach and organize like David “the Godfather of SF Skating” Miles and Richard Humphrey in the East Bay.

I’m so grateful that I get to benefit from and participate in these Black dance forms.

Thanks to folks in the Roll Out: A Roller Skate Collective Facebook group for links and suggestions for this piece, particularly Slab Bran.

Sources for more information and inspiration:

- And the Beat Goes On: A beautiful New York Times article on rhythm skating, with an accompanying video on JB Style.

- Meet Bill Butler, the Godfather of Roller Disco: A profile in the NY Times of one of the most influential Black skaters of all time.

- United Skates: a powerful and sobering documentary about Black skating in America.

- Roller Skating, Civil Rights, and the Wheels Behind Dance Music: A history of skating and its deep connection to dance music.

- Where the Music Rolled on: Roller Rinks, Hip-Hop’s Forgotten Stage: a dope history of how the history of hip-hop is tied to the history of roller rinks in America.

- The Last Adult Night at One of New York’s Last Roller Rinks: a tribute to Hot Skates in Long Island, which closed in May 2019.

- The Difference Between Rolling and Skating: Style: Includes descriptions of different skate styles including JB, Bill Butler’s “Jammin”, Fast Backwards, NY Style, Snapping, and more.

- Rhythm Skating History: Atlanta, Detroit, and Cleveland Styles (video): Dunbar breaks down his research into different skate styles from around the US.